The Significance of the Refugee Deaths at Wimeraux

Tonight at the vigil for the five young Syrians who died at Wimereux on Sunday, I met the brother of one the people who was lost. He is still shocked and numb, disbelieving that the journey they made together has ended like this, in horror just 20 miles from their destination. He is in his twenties, now left alone in Calais – the rest of his family are still in Syria.

His brother was 14 years old.

In the biting cold and dark, you could feel how Sunday’s tragedy, together with numerous other rescues and near-fatalities along the coast, has hit Calais hard.

Perhaps that’s because of the awful way these young people died in the icy cold sea.

Perhaps we’d all begun the year subconsciously hoping 2024 would somehow be better.

For me it’s all this, but it’s also the growing awareness of the violent forces behind this tragedy.

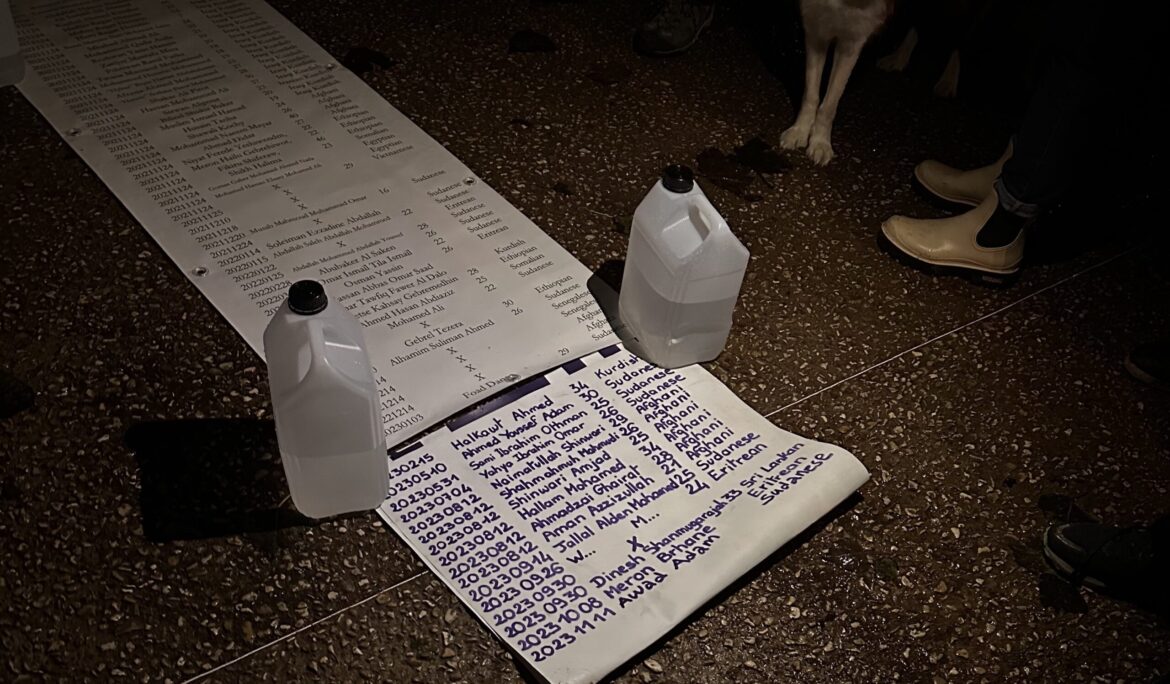

It is impossible to say for certain how many people waiting to cross from north France to the UK die in each year, but most of those who try to keep count put the figure at around 30. They would also roughly agree on that being a 30% increase on 2022.

That’s a similar figure to the 36% decrease in the number of people arriving in the UK safely by small boat in 2023; somehow it seems not entirely coincidental.

Since last summer the authorities in France have been more aggressive and intimidatory in their evictions, harassment of refugees and aid workers, and prevention of departures in small boats. We meet people whose boats have been slashed in the water. We know people have died in panics instigated by riot police. We know groups are leaving from less-policed places, making longer and more dangerous journeys.

People take greater risks, and suffer worse attacks. Hardly surprising, then, that the death and injury counts rise.

The UK and French authorities sanitise all this by crediting technology. The UK paid France €72.2m to police its border in 2022-23, and last Louis-Xavier Thirode, Prefect Delegate for Security, claimed it was new drones, vehicles and night-vision tech that had allowed him to reduce the crossings. It sounded so much nicer than beatings and boat-slashing.

To us here it seems very much that any reduction in small boat crossings is being bought with old fashioned violence and intimidation towards Calais refugees. And that makes it clearer than ever that the only way of ever reducing them safely will be by introducing safe routes.

Until that happens, I am deeply sorry to say, we will continue to gather at vigils in the cold and dark in Calais, listening to laments for brothers and sisters and friends among the Calais refugees who sought only a safer and more normal life.

Imogen Hardman, Care4Calais Senior Operations Manager, Calais

Support our campaign for safe routes for refugees: care4calais.org/safepassage/